Dhandak The elite strata having traditional basis of power and influence does not give opportunity in the circulation of power elite, nor it paves way for emergence of the new elites. In the feudal setup, masses did not have counter elite to challenge the ruling class. Yet there had been some sort of socially legitimate device which provided to the common masses an opportunity to raise their voice of protest and express discontentment against the ruling authority. By way of organising ‘dhandak’, the masses would seek solution of their grievances. ‘Dhandak’ as a form of mass-protest prelude that the subjects had the right to approach the raja for redresselof grievances raised against the officials, jagirdars or thokdars. Thus ‘dhandak’ as a device used to set right the differences and conflicts of interest occurring between the state and the subjects. It was also a means to regain those popular rights and customary privileges which at time were usurped by the state.

In protest, the villagers would create unruly situation – disobey the laws of the state, let their cattle roam freely in the corn fields and go to the ruler in bunches to complain against the injustice, violation of rights or accesses committed by jagirdars and thokadars or state officials. This was the practice prevalent in the princely state of Tehri known as ‘dhandak’. This form of mass movement did play its role in the interest of peasantry.

Movements in Saldana and Rawin

The reaction of the people against injustice perpetuated by the feudals was witnessed for the first time in 1835, when in Saklana jagir the villagers raised their voice. Under Regulation 10 of 1817, the Saklana jagirdar enjoyed police powers, in all matters relating to jagir he was answerable to the British (Commissioner of Kumaun, who was political agent of the East India Company in Tehri). The jagirdar of Saklana started collecting excessive revenue. The revenue fixed by the British was Rs. 730 per annum, but the practice of realising unauthorised revenue reached the sum of Rs. 1300 in 1835. Besides this unpaid labour from the villagers of Saklana, forced them to come out of their hilly region with clock and cudgel, and enter the court of Major Young at Dehradun. They stated in their petition that illicit collection of taxes by the jagirdar had increased beyond their means .

On the recommendation of Major Young on February 7, 1838, the Board of Directors of the East India Company decided to put the jagir under direct control of the ruler of Tehri for all purposes. Henceforth, no complaint regarding the jagir was to be entertained by the Political Agent and the villagers were directed to first approach the raja of Tehri for resolution of their grievances.

Govind Singh Bist, the ‘founder’ (Chief) of Rawain, following the example set by Saklana jagirdar, also started to abuse his authority by collecting heavy taxes from the villagers. His cruelty surpassed even the Saklanies. In the case of non-payment he would sell cattle, women and children of the defaulter to obtain the expected revenue. The villagers, as a means to express their bitter feelings organised ‘dhandak’.

Peasantry Movement

The reign of Bhawani Shah (1859-71) was marked by the peasant awakening in the state.

The pioneers of the awakening were Badri Singh Aswal and Shiv Singh Rautela. In seeking relief from increased revenue ‘dhandaks’ occurred when a violent uprising was initiated by Balvadra Bistand Nand Ram (9). In consequence of this uprising the raja was compelled to give relief from taxation. Aswal, the leader of the movement, later on was falsely implicated in a case and arrested. The court of raja sentenced him for six months imprisonment with a fine of one thousand. Aswal, against his arrest, appealed in the Court of Henry Ramsey (political agent) where he was found innocent. However, before he could be set free, he breathed his last (1868)

Unrest in Saklana ‘ During the rule of Kirti Shah (1887-1913), the people of Saklana jagir again expressed their resentment against the jagirdar. This time besides excessive revenue and forced labour, the jagirdar on his own imposed restrictions on the use of forests, which deprived villagers of their traditional rights. While opposing these practices, Roop Singh Kandari, who was a ‘sayana’ in a village in Saklana jagir, emerged as the leader of the masses. Roop Singh wanted the jagirdar to follow the British rules in dealing with the villagers instead of age old feudal practices. Raja Kiriti Shah, ultimately had to intervene in the conflict and on getting fIrst hand information the raja informed the Commissioner of Kumaun about the misdeeds of jagirdar. Consequently, the magisterial powers of the jagjrdar were withdrawn from him and, entire forest area was put under the direct control of raja.

Coolie Begar movement

According to the Regulations of Fort William, whenever the British officials toured the hills, it was regarded as the duty of the local people to arrange coolies for their luggage. This was known a Coolie Utar; it was compulsory and the status and the condition of the individual concerned were not kept in view. Not only for the officials but also for their vast entourage of servants and the British tourists, coolies had to be arranged without payment.. Then there was Coolie Burdayash and in this system, free ration had to be provided to the officials on tour, and the people were penalized if they failed to do so. According to Coolie Begar the hill people had to work for the British officials on tour without payment. For public works too, bonded labour was enforced during British times. There was a lot of resentment against these social maladies and ultimately the people succeeded in eradicating them through a mass movement in Bageshwar on 13th January 1921.

Dola Palki movement

Doms struggled to improve their status. Artisan Doms who could improve their economic condition claimed a higher status among Doms. They joined the Arya Samaj and became Arya, adoptedjaneo and got purified. Lala Lajpat Rai in 1913 visited Almora and in Sunkiyan village gave Janeo and dvij status to 600 untouchables. A temple was opened for untouchables in Almora. There was a Dola-palki movement by the Doms. During the marriage of Doms the bridegrooms and brides were not allowed by the higher castes to use dola and palki (palki was used to carry the bridegroom and dola the bride. Both dola and palki were carried by 2 to 4 persons on their shoulders) and were instead to walk on foot. When Doms asserted their right to use dola-palki there was often violence. The Arya Samaj played an important role in the movement. Doms also asserted that they should be called Shilpkar. Tamtas (copper smiths) who became rich took to priestly function amongst shilpkars. 45 The Kumaun Shilpkar Sabha and the Garhwal Shilpkar Sabha spearheaded the movement for status mobility.

The University Movement

In the decade preceding the year 1971, the demand for a University in the region was discussed so much in the local press that it was not difficult to build up a movement around this issue. During the summer of 1971 the youth of Srinagar took initiative in this direction and formed an organisation, named Uttarakhand Viswa Vidyalaya Sangharsha Samiti (UVYSS), which was wholly confined to the issue of the University.

The entire movement which began in 1971 and came to an end in 1972, is in a way a story of UKVSS, the ups and downs of the struggle and finally the establishment of the University. On its formation the immediate task before the UKVSS was to convince the State Government that the University should be located at Srinagar. The younger leadership that prevailed over the elder generation believed that the ordinary channels through which the demand had been pressed before were not very satisfactory. To them the right approach would be direct confrontation with the authorities and nothing else.

The movement began with relay hunger strike at Birla Government College Srinagar and gradually widened the scope and methodology coyering almost entire Garhwal region. Swami Manmathan, who emerged as the central figure in this movement took the movement right upto village level by seeking cooperation and participation of Block Pramukhs and other village elites. Indefinite fast, ‘gherao’ and ‘bandh’ were frequently organised at various towns and routes of pilgrimage from Rishikesh to Badrinath and Kedamath were used to sent the message of movement outside Uttarakhand through leaflets distributed and circulated to outsiders – tourists and pilgrims. The opening of Garhwal University ultimately was announced by Mrs. Indira Gandhi on October 9, 1973, at Srinagar. And on December 1,1973, a gazette extraordinary announced the decision of the U.P. Government to setup the two universities – one at Nainital and the other at Srinagar (Garhwal).

Chipko Movement

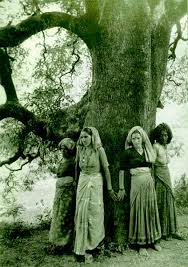

The Chipko movement took birth on March 27, 1973 in Gopeswar in Chamoli district of Garhwal division, when one Satvodaya worker, Chandi Prasad Bhatt organised the people to oppose commercialisation of forests. People of the region were deprived to use ash tree for agricultural implements. These trees were sold by U .P. Government to Simon Company of Allahabad to make sporting goods. The people reasserted their rights over the forest products. The movement was initiated for the first time in the forest of Rampur Fata. The method of Chipko was simple – villagers would hug the tree when the lumberjacks of forest contractors were approaching to fell them down. The event of Rampur Fata was followed by Chipko in the forest of Reni in Chamoli district. This event was marked by the leadership of Gaura Devi – a village women who led the women folk to save the trees. The initial objective of this unique movement was to save the hill forest from exploitation by the outsiders, and the organisation for achieving this objective then came to be known as ‘Uttarakhand’ Sangharsh Vahini (UKSV)’.

In 1977, within the movement a division appeared when protagonist of Chipko movement, Sunder Lal Bahuguna started proposing total ban in felling. His contention was that deforestation had caused ecological problem, thus dependency of locals on forests for their needs and total ban on felling due to ecological reasons; these two contradictory objectives came on the surface. In 1977, the issue of denudation came under wide discussion and it covered various shades of opinions. The issue was debated and publicized in the local and national press extensively. Thereafter Sunder Lal Bahuguna took the lead of the movement and it became a movement for ecology. The government of U.P. resorted to force in leasing out forests to contractors for commercial purpose. In Hewal Ghati and Salhet forest areas in December 1977, Chipko was introduced.

The U.P. Government had to send PAC to assist contractors and forest officials. The elected representatives however were in tune with government policy. The elite section forming part of non-governing elite – a section of Sarvodaya and CPI leaders supported the Chipko. The movement succeeded in placing ecology at the centre stage while forming forest policy. Its impact on decision making at national level cannot be undermined, though it began with ‘local needs’ to be preferred over commercial use of forests.

Separate Hill State

After independence the issue of separate hill state could not get sufficient support as the power elite at the higher level did not favour it. In 1946, Badri Dutt Pandey demanded separate hill state, which was turned down by the then Premier of United Provinces G.B. Pant, as U.P.’s dominance over national politics owing to largest number of M.P.’s from this state would have suffered after division of U.P. This policy of domination over national politics remained a central cord of the Congress party right from Pant to Tewari. General Secretary of CPI P.C. Joshi, time again demanded autonomy for the hill region. Manvendra Shah ex-ruler of Tehfi state in his capacity as M.P., also raised the issue of separate hill state. Counter elite from the region over the years after independence made efforts’ in this direction – submitted memorandum to the P.M., organised conferences, rallies and protested on various occasions to draw the attention of power elite. Dharna and demonstrations at Boat Club by separate hill state protagonists were frequently organised from time to time, yet no central organisation conclusively setup for the purpose, with full strength did emerge. However stray events in this direction not only kept the issue alive, they educated the masses to a large extent . and helped in forming collective psyche of the hill people to strive for separation from U.P.

On 24-25 June 1967 ‘Parvatiya Rajya Parishad’ was formed under the leadership of Oaya Krishna Pandey. This may be taken as a solid organisational step in achieving the objective of separate hill state. Narayan Dutt Sundriyal, Communist leader of CPI took over as Secretary of this organisation. It was in 1968 that the Prime Minister agreed to have a separate Planning Cell for the hills. In 1970, P.C. Joshi formed one organization named ‘Kumaun Rastriya Morcha’ to achieve the objective of separation of hill region. It was in 1971 that ‘Uttarakhand Rajya Parishad’ was reorganised and Pratap Singh Negi (M.P.), Kripal Singh, Sridhar Chamoli and K.S. Negi along with Narayan Dutt Sundriyal became active and subsequently Narendra Singh Bist (M.P.), Indermani Badoni (MLA), Meharban Singh (MLA) and Captain Shurvir Singh joined this organisation. In 1978, Trepan Singh Negi a prominent leader of Tehri joined. the organization. During Janata Party regime on January 13, 1979, under the banner of ‘Uttarakhand Rajya Parishad’ a prominent section of elites including Manvendra Shah, Khushal Mani Ghildiyal, Trepan Singh Negi, Puran Singh Dangwal, Suman Lata Bhadola, Pratap Singh Puspan, Pratap Singh Bist, Baba Mathura Prasad Bamrara, etc. participated in a demonstrated at Boat Club.

Formation of Regional outfit: Uttarakhand Kranti Dal (UKD): On July 24, 25 Dwarika Uniyal a prominent journalist convened ‘Parvatiya Vikas Jan’ Sammelan at Mussoorie. This Sammelan was attended by socially active and reputed persons including Nitya Nand Bhatt Dr. D.D. Pant, Jagadish Kapari, N.K. Uniyal, Lalit Kishore Pandey, Vir Singh Thakur, Hukum Singh Panwar, Diwakar Bhatt, D.P. Uniyal, Vinod Chandola, Vinod Barthwal, and Devendra Sanwal.

It was in Anupam Hotel Mussoorie on 25th July 1979 that Uttarakhand Kranti Dal, the first regional political outfit was formed. Dr. D.D. Pant, a prominent educationist and ex-Vice Chancellor of Kumaun University took over as the first president of the party.